Most of what divides the opinions of students of the Bible and the doctrines they embrace revolve around how they read Scripture. As Scripture has been given in a variety of formats, IE: From a prophet directly from God; Prophesy from Jesus; As an internal discussion as a person reasons with himself in light of His Word; Wisdom Books like Proverbs and Psalms; The directives of God to Israel through Moses in the Torah, the first five books of the Old Testament; Historic interactions and reports. Most everyone can agree to distinguish promises specific to the people addressed versus the promises as affirmations of God’s intent to all who belong to Him through faith in His Messiah. We recognize the importance of understanding the historic context of the original listeners and seek reasonable parallels to us today. There is no objection to parsing out the original Hebrew or Greek to discern the meaning of the Words. The problem hinges on whether a literal reading versus spiritualized (allegorical) understanding of the Scripture is warranted.

This is a critical question to answer because an inferior approach can wrest God’s intended meaning and put it in the hands of us as fallible sinners. If He is the Giver of the Words, should we hazard injecting our own meaning into His Message?

Scholars through the ages have recognized guidelines and methods for studying the Bible that cooperate with God’s intent and help us understand what He’s said. These aren’t iron clad but are important principles to protect us from straying in our interpretation of ‘regular’ and prophetic Scripture.

A. Interpret Scripture Literally

This principle is first and key to understanding Scripture, just as we would understand any other literature or regular conversation. God, with the aid of His Spirit, speaks His higher thoughts to us plainly because He wants us to understand.

The literal method of interpretation is that method that gives to each word the same exact basic meaning it would have in normal, ordinary, customary usage. … It is called the grammatical-historical method to emphasize… that the meaning is to be determined by both grammatical and historical considerations. J. Dwight Pentecost, Things to Come

Each word is understood as it’s same basic and customary meaning, determined by its grammatical and historical use, accepting the rules of grammar and rhetoric in light of the cultural and historical environment of the time it was written. This includes figures of speech just like we use today such as “There were a million people in the house.” Obviously not literal but it is a literal-idea figure of speech conveying there were many people.

Elliott E. Johnson, “Premillennialism Introduced: Hermeneutics” explains:

“As an example, “serpent” as a word normally means “animal” and only an animal. But this normal usage and sense does not legislate that “serpent” in Genesis 3:14 must mean merely an animal. On the other hand, a literal system begins with recognizing “serpent” as an animal. Then it looks to the immediate or extended contexts for other clues to the meaning. This serpent speaks (3:1–5), and speaks as the enemy of God. Thus, in the literal system, this serpent is more than an animal; it is God’s enemy…”

Without beginning with a literal mindset approach we risk the interpreter taking the position of final authority. Allegory or spiritualizing the text is not grounded in the closest proximity to fact and the text is at the whim and imagination of the interpreter.

“The literal system is necessary because of the nature of Scripture. First, Scripture is sufficiently clear in context to express what God promised to do. Second, Scripture is sufficiently complete in context to establish valid expectations of the future acts of God.” (Johnson)

Further, human spiritualization and allegory beyond Scripture is an unholy guise unto which to alter the statements and intents of Scripture supporting a false doctrine. The essence of the method is reassigning God’s intended meaning to suit the spiritualizer’s narrative as he holds authority in the hearer’s eyes, speaking in terms that appear to make sense. Spiritualizers redirecting God’s Word dupe listeners who lack sufficient Biblical literacy and discernment to fend off their fabrications. These false teachers introduce half-truths in the way the Enemy did in the beginning, at the Fall. If this seems a hard stance, consider God’s command regarding false prophets responsible for delivering His Words verbatim. (Jeremiah 23:16) Bible teachers, while not under direct revelation from God, are responsible much the same to faithfully convey His Scripture. False prophets faced death (Deut 18:20), while false teachers today risk a harsher Bema Judgement (James 3:1) or even be found to not belong to Him. (Matt 7:19–23)

B. Interpret Scripture in comparison to other Scripture

This follows the Reformer’s central principle of Analogia Scriptura, or the Analogy of Faith. The Westminster Confession states: “The infallible rule of interpretation of Scripture is the Scripture itself: and therefore, when there is a question about the true and full sense of any Scripture (which is not manifold, but one), it must be searched and known by other places that speak more clearly.”

As Scripture is the Word of One Author, of one mind as well as Divine, His Scripture cannot contradict itself and so is qualified for proof and clarification of the rest of Scripture. This includes the interconnection of the Old and New Testaments. While the OT provides the lion’s share of the basis for our understanding, the NT provides both further details and new information. Neither is inferior to the other and both must be employed in reference as literally told. Spiritualizing OT passages to reassign the related NT information is not how God intends us to read Scripture.

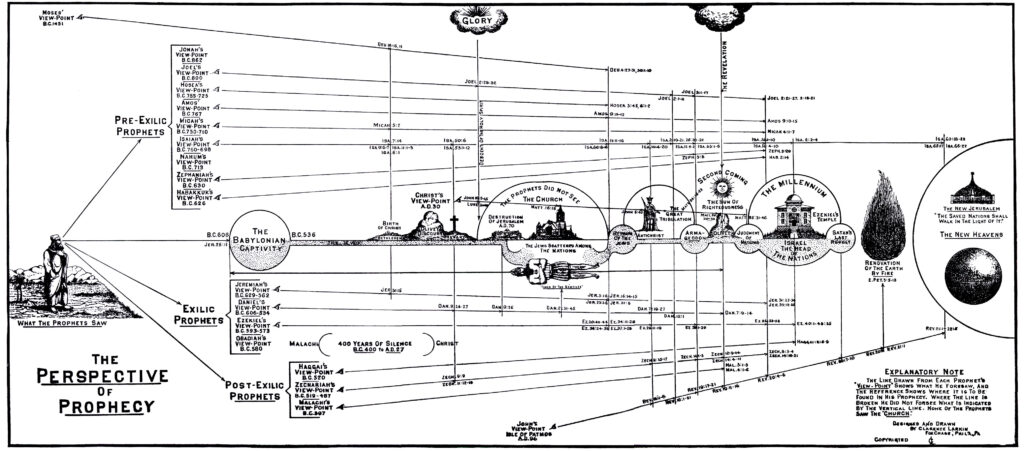

C. Interpret allowing for time intervals

Prophetic Scripture only assures us of one aspect of the future declared by God, that something will happen. He does not always tell us how He will do something or when on the calendar. Prophets, with the general exceptions of Daniel and the Apostle John, are usually told only the terminus point. This essentially means prophesy is often without reference to depth of time. For instance, the earliest Scripture foretelling of the Messiah is Gen 3:15 followed by at least Deut 16:18, Deut 18:15, Isa 11:1-3, Isa 7:14, Isa 9:6-7, Dan 9:24-25 and Micah 5:2. Except in Daniel 9, the prophet only sees a linear one-dimensional reference point. They can’t triangulate to a specific date, and the duration of intervals between points in a prophesy – sometimes separated by a comma in a sentence – are unknown.

These are often milestones that confirm the next juncture has passed. We might be told there is a next milestone, but not when it will happen. The establishment of national Israel is an example. Spoken of in Isa 11-11:16, Jer 16:14-15, Jer 23:3-8, Jer 23:7-8, Jer 3:18, Ezek 20:40-44 and Amos 9:11-12, the earliest is about 2700 years before the fact.

D. Interpret Figurative Language Scripturally

Just as Scripture is used to interpret Scripture (B), prophetic symbols and figurative language given to convey an idea of God should be viewed in three contexts: The Immediate, the Larger, and the Historical. A literal mindset and contextual cross ties to other Scripture give a reliable basis of interpretation, guarding against allegory and spiritualization which are the ideas of the reader overlaying the thoughts of God.

Spiritualization is a risky approach as there is less factual basis and it opens the door to distortions of God’s message. More concerning is it removes the basis of validity in that each allegorical interpretation is as valid as the next. Also, in mixing literal and allegory, where is one approach used over the other, who is to choose? The interpreter, seeking to assign his own framework of past events and extrapolate Scripture into the future, is the arbiter of meaning who has cut the moorings of plain reading of contextual Scripture.

In Jesus’ Revelation to John, the contextual method relies heavily upon the interpreter’s Old Testament knowledge. The Jews of John’s day were well grounded in their Scripture and would have clearly understood many of the Old Testament Scriptures Jesus refers to in the vision. Merrill C. Tenney, Interpreting Revelation notes:

…a count of the significant allusions which are traceable both by verbal resemblance and by contextual connection to the Hebrew canon number three hundred and forty-eight. Of these approximately ninety-five are repeated, so that the actual number of different Old Testament passages that are mentioned are nearly two hundred and fifty, or an average of more than ten for each chapter in Revelation.

Without clear and reliable interpretive principles, we cannot expect to arrive at a clear understanding. Even if the literal contextual method fails to give a clear understanding of the Passage, would we agree that it is a far better outcome than an answer void of God’s intent? And being subjective to the interpreter, isn’t the truth at risk of being maligned by the fallible human imagining it? Could there be a more dreadful outcome?

For a more thorough discussion, see Benware – Summarized Chapters, Interpreting Bible Prophesy as well as Chapter 1 of Benware’s Understanding End Times Prophesy: A Comprehensive Approach.